How Play-A-Longs Came Along

Content for this section comes from 2021 interviews with Jamey Aebersold about his Play-A-Longs business and other recent artist/educator interviews, unless otherwise noted.

Saxophonist/jazz educator Jamey Aebersold produced his first Aebersold Play-A-Long record in 1967 with $500 from his parents, a hand-drawn cover, and a sound idea.

“Play-A-Long recordings had been in existence for some time, but Jamey’s method was all-encompassing,” explained drummer Akira Tana, who is featured on three Aebersold Play-A-Long recordings.

“It was organized in such a way that all instruments could benefit. It was offered in different keys. The Play-A-Longs also focused on material from specific artists, such as Sonny Rollins; Herbie Hancock; Horace Silver; Duke Ellington; Miles Davis; Wes Montgomery, and Joe Hendeson.

“In addition to offering different viewpoints from a composer’s perspective, the Play-A-Longs also offered material to study in a variety of keys, ‘feels’ and tempos, including major and minor blues in different keys. This was very informative and connected the dots and crossed the ‘t’s in the chordal and harmonic scheme of things,” according to Tana.

To promote the first Aebersold Play-A-Long, “Jazz: How to Play & Improvise,” Aebersold bought a two-line classified ad in teeny type in DownBeat.

“And then I went out and did a lot of clinics,” Aebersold said in a 2019 interview with Matt Oestreicher on the Mindful Musician program. “I took my record player and I took the LP with me and I demonstrated to people how you could practice the scales and build a solo.”

He hoped that the Berklee School of Music, which was publishing jazz material at the time, might be interested and take it over. That didn’t happen.

“For the first 11 years or more, I did everything myself—the packaging, the writing and the promotion.”

So, Aebersold went to work on a second volume, “Nothin’ But Blues,” thinking he would move on to something else.

“I think (pianist) Dan Haerle said, ‘Well, why don’t we do the II-V7-I progression,” Aebersold told Ostereicher. “And I’m thinking, ‘Who is going to want practice with that in all 12 keys? You know, that’s not what I had in mind, although I realize it’s one of my best ones pedagogically.”

Now, Aebersold was knee-deep in jazz education publishing and recording.

Volume 4, “Movin’ On,” which featured original songs by Haerle and Aebersold and Volume 5, “Time to Play Music” with more Haerle tunes in the style of standards, followed in the first decade of Aebersold Play-A-Longs.

‘That got us from 1967 until 1975 or early 1976. And that’s when I got in contact with a lawyer who took care of songs for Prestige Music in Berkeley, CA,” Aebersold said.

“He said, ‘Yeah, we can get you hooked up, Jamey. You can use some Charlie Parker tunes, some Miles Davis tunes and some Sonny Rollins tunes. That was Volume 6, Volume 7, Volume 8. I tried to pick the tunes that were available to me that everybody wanted to play.”

Jazz educator Pat Harbison, who started taking lessons with Jamey when he was 13 and has been Professor of Jazz Studies at Indiana University since 1997, saw the Aebersold Play-A-Longs business grow first hand.

“To watch those first five volumes, that’s where the business model was sort of transformed and the product line was going to emerge unbidden. It was really an evolution.

“And on the other albums where he couldn’t get the rights, he could write his own contrafact melodies and still put the chord progression on because you couldn’t copyright the chord progression,” Harbison explained.

Aebersold continues the narrative. “When we got into Volumes 6, 7,8, Volume 9 was Woody Shaw, which was much more advanced. Number 10 was David Baker, which was more advanced. At that point I’m not sure how we morphed into Herbie Hancock. Oh, I think it was Hansen Music down in Miami, FL. We hooked up with a guy there and he said, ‘Yeah, we can draw up a contract for those tunes by Mr. Hancock.”

“And then I called somebody, or maybe a couple people, and got permission to do Duke Ellington and I talked to Cannonball Adderley in person, and that’s how we got going. And they would help me pick the tunes. I would pick the tempos and the musicians I thought would do a good job playing on those tunes.”

By this time, the Aebersold Play-A-Longs were well established and Aebersold was able to bring musicians in who were playing gigs in nearby cities (Louisville, Indianapolis, Chicago, Cincinnati) to record the Play-A-Longs in his basement studio. And as jazz faculty joined Aebersold’s summer jazz camps, they become a regular “studio band” of rhythm section players.

Some early volumes were recorded in New York City, and Tony May was the studio engineer. They used 1/2-inch tape and most takes were done the first time,

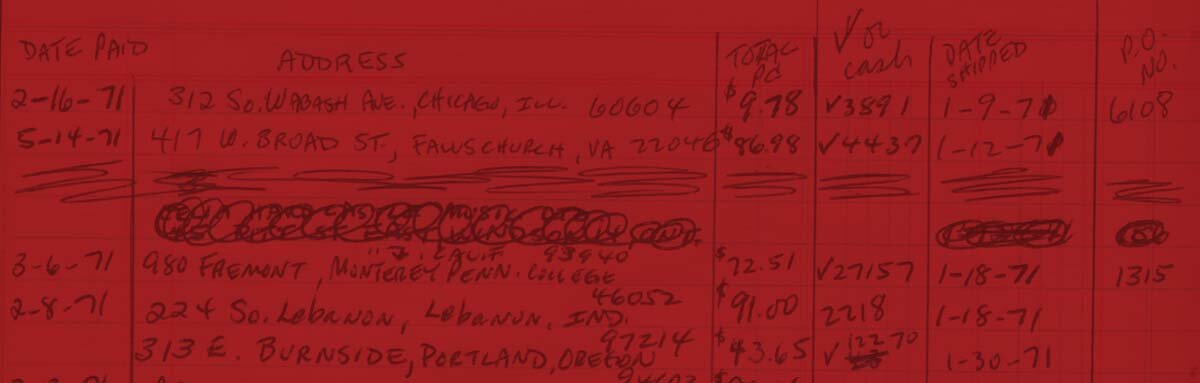

“For the first 11 years or more, I did everything myself—the packaging, the writing and the promotion. My aunts started working with me at some point, and they’d write down everything by hand, ‘So-and-so ordered Volume 1,2,3, and 17,’” said Aebersold.

“And I’m thinking, ‘Who is going to want practice with that in all 12 keys?’ You know, that’s not what I had in mind, although I realize it’s one of my best ones pedagogically.”

50,000 students have taken part in Jamey’s jazz camps, workshops and clinics.

Later on, he added more staff to pack orders, handle the inventory and answer the phone. Three of these people started working with Aebersold while they were in high school and are still with him over four decades later.

As for the basement studio recordings, Aebersold was a stickler for precision and quality. Proofreading was an important part of the process.

“When people talked about an Aebersold Play-A-Long, I didn’t want them to ever say, ‘The chords are wrong,’ like some of the Fake Books were, or the melodies were wrong.”

In an era of advanced digital recording technology, it is difficult to fathom how well these recordings have stood the test of time, despite the fact that they were made in Aebersold’s basement.

“At first we had the piano, bass and drums in the same room,” said Steve Good, who was the engineer for the recordings. Then, the bass player was moved behind a large bookshelf with books on either side. The drums were in the same room as the piano.

Good built a removable wall to make a “room” around the piano. None of the players could see each other.

Some years later, Aebersold added to his house and expanded the space in his basement. That enabled Good and Aebersold to really separate the musicians. Again, they could not see each other, but they all wore headphones.

“At some point, I got the bright idea to borrow some little microphone mixers—this wasn’t until the early 1990’s,” Good recalled. “Everybody had their own little mixer for their headphones. They could turn themselves up nor down on their own and I didn’t have to adjust it for them. That worked pretty well.”

“The separation had to be really good or the trick didn’t work of using the balance controls,” Good noted. “Really, we had to fuss with that a lot and it was kind of a problem until we got everybody in their own separate room.”

Good said he never used reverb in the recordings. “They were dry recordings. Somewhere in my mind I thought that reverb might really interfere with the pedagogical (purpose) of the recordings.” Amazingly, most of these basement studio recordings were done in one take.

From inception to distribution, each volume took five to six months to complete, Aebersold estimated.

Today, the Aebersold Play-A-Longs continue to guide the practice of jazz improvisation technique and jazz/standards repertoire.

Saxophonist and jazz educator Pat LaBarbera remarked: “Because of the proliferation of his product all around the world, when you sit in with somebody, chances are that you’re playing from one of Aebersold’s lead sheets from one of his books. So, if you’re learning “Nica’s Dream” and you’re going somewhere to sit in, most people probably learned the tune from an Aebersold Play-A-Long.”

“The Play-A-Long will be around,” agrees bassist Rufus Reid, another of the legendary musicians who played on many of the recordings.

“Even after all of us are gone, I think the music, the idea, and the concept (will endure). There will always be players coming up wanting to be able to play and no one is (always) going to be able to play with great players.”